Butte Magic of Ignorance

Treatment Part 2

Emily sits on a bench along a street. She is paging through the newspaper sprawled between her hands. "Nobody's hiring uptown," she says to herself. "I'll have to check out the fast food places and stores down on the flats." She drops the newspaper to look up at the mountain, and at the dot high on top of it. She folds up the newspaper and uses it as a shade to keep the sun out of her eyes, and so she can better see the white speck that catches the sun and glares it back into her eyes. As she is looking up a bus pulls up. The door opens but Emily doesn't notice; only when the driver begins closing it does she see the bus, stands up and runs into it.

Irene has her box of family heirlooms with her at the archives. She reads a line from a letter and compares it with a specific days' stories and ads in the newspaper yellowed in its big bound book on the table in front of her. "Who was Mary Harrington?" Irene thinks. "Was she a miner's wife, trapped in a dreary life, her day spent on chores, trying to clean the pollution of hard rock mining out of her husband's other pair of longjohns, trying to raise children in a city with soil so toxic that trees could barely grown in it. Did she spend her days anxious over whether her husband would make it through the workday or perish in a cave-in so deep below the earth. Did she spend her nights smelling the sweat and feeling the heat of her husband, wondering if tomorrow would be his last day. Did she long for her home across the sea, the family she would never again see. Could she even imagine the possibilities that her life held when she spent it in so much repetition?"

As Irene meditates on her great-grandmother, she imagines herself as the woman, dressed in a plain dress of the early twentieth century and a long apron. She kneels in front of a tub of steaming water and scrapes a pair of blackened longjohns on a washboard to clean them.

"Was she a prostitute, spending her nights serving beer to miners and taking them into small rooms to earn spending money down on Galena Street. Or was she one of the young women, the higher-class companion prostitutes that made such an impression on the young Charlie Chaplin. Did she wear fine things and hold some control over her life, never drinking alcohol, but occasionally traveling a block down to Chinatown to buy the medicine needed to clean up one venereal disease or another. Facing a long line of miners, men who could never wash the smell of 1,000 feet below the earth's surface out of their bodies, men with tragic contentment in their faces, dangerous men, men who saw so little future in such a risky occupation that they really did live only for today. Was she able to find herself in a life so revolved around the needs of men, her customers. Was she able to read magazines and books, did she long for a life away from Butte, was she saving her money for some kind of release, and did she get married to a miner rather than continue a career in which her economic value decreased with age, dying of some miserable disease with only the opium of Chinatown to ease her pain and lead her to dreams of some other equally pathetic life?"

As she meditates on this she imagines herself as her great-grandmother. She is dressed in a fine period dress and walks down the sidewalk, past brick buildings, past the last structures of Galena Street, past the windows of the small rooms where the prostitutes once did their business. Today the rooms are cubicles in an antique store. In one cubicle she finds a stack of men's magazines, and pages through the centerfolds and photographs.

Emily is down on the flats, walking up to a fast food restaurant surrounded by its little moat of asphalt. She examines a newspaper ad looking for an employee, team player, good attitude, for a fast food franchise. She imagines herself in a fast food shirt and hat, pressing down burgers at a big metal grill. She looks up and sees a large statue of the virgin Mary standing, as if waiting for her meal. Emily rushes to put together a burger, putting the meat on a bun and trying to add the condiments. But she makes a mess of it, dampening it with too much ketchup, smearing all the pieces together until the bun is in scraps. She wraps it all in a paper wrapper but messes up there too. She keeps looking up at the Virgin Mary statue, and seeing the statue look down makes her even more nervous. The wrapper is in shreds, as is the burger by the time she has finished and hands the mangled messy thing to the Virgin Mary Statue. An arm comes out of the statue and accepts it.

Emily looks up at the dot on the mountain and then down at the newspaper again. She stands in front of a mall and looks at an ad for a sales clerk in a mall shoe store. She imagines herself walking out of a closet at a store with a box of shoes in her hand. She walks out to her customer and shows the customer the shoes in the box. The customer looks at the shoes, the customer is the Virgin Mary statue. Emily attempts to put the shoes on the cast iron end of the robe, which is the bottom of the Virgin Mary, but she can't. She sweats and keeps looking apologetically at the statue but the face of the statue remains immobile. Emily checks the size of the base and tries the shoes again, and in her attempts to make the shoes fit she ends up ripping the shoes to shreds.

Irene sits at the table in the archives, spreading the letters out over a map of the historic city of Butte. "Maybe Mary Harrington was a reformer," Irene thinks, "a politically active woman, a fighter in the temperance movement. Did she go to bars to admonish the men drinking there. Did she organize meetings with other temperance fighters, mostly other women, to discuss the destruction caused by strong drink. Did she picket saloons and assist Carrie Nation on her drive to smash liquor bottles and the liquor industry. Did she celebrate and pray hard in victory after the passage of the Volstead Act and prohibition became the law in the United States. Did she watch as the liquor industry went underground, as bars stayed open around the clock, their only change being the bottles of pop that were set up in front of the bottles of hard alcohol, harder because of its illegality. Did she notice as the liquor industry turned into a cottage industry, as many people built stills in their basements, producing an alcohol much more dangerous than the industrially produced stuff. Did she see the rise of organized crime, as liquor distribution turned into a profitable line of work for desperate people, and how the mass of the city turned into such desperate people, finding little respect for a law that was so easily broken, so contemptible."

Irene imagines herself as her great grandmother, dressed in a conservative long dress with an enormous hat. In one hand she holds a protest sign, in her other she pours out the contents of one bottle of hard liquor after another.

Emily walks into a large surface parkinglot. Her eyes are fixed up at the mountain but she looks down at the newspaper as she walks toward a low one story prefabricated industrial building. She looks down at the paper and sees an ad for line worker at a manufacturing plant. She imagines herself sitting behind a belt moving with small articles going past her. As one passes she grabs it and attaches a small piece of plastic. She looks up and the Virgin Mary statue walks past, watching her work intensely. Emily gets confused from the presence of the statue and misses one of the parts that goes by, then tries to reach over to get it but breaks it when trying to put on her piece. When she sits down again at her seat she reaches for the next passing article but sees instead that it is one of the figurines from her collection. She tries to put her piece on it but it will fit nowhere. She sets it down and notices that all the other articles coming on the line are from her collection. She tries to put her piece on some others of them but nothing will fit. She looks back up at the Virgin Mary statue that is patiently watching her work.

Irene leaves the Archives, her box of articles in a bag hung on her shoulder. The headphones play an old fashioned record, a tune from nearly a hundred years ago. Irene walks down a street of uptown Butte. Then she's walking, but she's in a period dress, as if it were her great grandmother walking down the street. She waves at someone ahead of her. That person is somebody standing at an uptown Butte corner in a period photograph.

At the house, Emily is vacuuming. She vacuums the same spot over and over and then stops the vacuuming a second to chop up some vegetables in the kitchen. Emily vacuums past the front door as Irene enters. She negotiates her way around the vacuum cleaner, in constant motion, and finds a seat in the living room. She takes out one of the old postcards from her box of things. Emily vacuums past and tries to see what Irene is looking at. When Emily comes by, Irene looks up from the card and slides it down her lap to the seat of the chair under her. When Emily has passed, Irene goes back to examining the card, only to hide it and look up when Emily passes again with the vacuum cleaner. Irene doesn't trust Emily enough to want to show the things to her, the things that mean so much to her, and Emily's inquisitiveness makes Irene want to hide them all the more. The music the plays in Ireneís ear is battered by static from the vacuum, as well as overwhelmed by its sound.

"Isn't that floor clean yet?" Irene says as Emily passes by yet another time. Emily looks down at the floor and walks away from the vacuum cleaner, leaving it running. She goes into the kitchen and chops up her well-chopped vegetables some more. She puts them into the blender on the counter and presses the button on the blender. The blender makes no sound. Emily lifts it up, turns it on its side and looks to where the power cord should be. The power cord has been cut off, it remains as only a bit of frayed wire near the base of the blender. Frank comes in, dressed in his miner's uniform, and walks past the vacuum cleaner that is still running. Emily looks up at him as he walks past. She feels something in a pocket of her apron and takes out some change. She separates the pennies and drops them in her penny jar, which is slightly less full than it was the last time that she dropped pennies in it.

Irene looks at the ancient postcard addressed to her grandmother. It is specifically addressed to "Hail Mary" Harrington. Irene reads the address and the short message on the card. "Hope you and John are well. I finally got my life settled down here in Helena but it sure is no Butte. All the best, Iris."

The sun comes through the living room window. Irene reaches over and switches off the vacuum cleaner, only to hear loud metallic clankings, as if somebody was moving around and dropping pieces of big equipment nearby. She sits up and watches Frank walk past her to the door with his miner's clothes on. He has a shovel slung over his shoulder. He opens the door and steps outside.

Irene quickly dresses and walks out of the house, looking down the street and seeing Frank walking a block or two ahead. She runs a few steps and follows Frank, keeping nearly a block's distance between them. He stops at a corner and looks partway behind him, but doesn't turn far enough around to see Irene. She watches him walk past the buildings of the city, past where they thin out and the headframes and scarred mountainside take over. She lingers behind a building and watches him ascend a hill and stop near a headframe. He takes his shovel to the ground and dislodges a rock. His pockets look full.

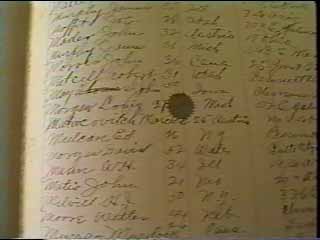

"John Harrington was his name," Irene says to the curator at the Archives. She has one side of her headphones propped behind her ear so she can hear, but music and announcements still play in the other. "My great-grandfatherís name. In one letter he is a miner, in another he keeps a bar, in another he just sits around all day. In one letter he is a hard-drinking man, in another he does not touch a drop."

The curator shows her a page of John Harringtons in a record book. "Do you know that your great grandmother only had one husband, -- I mean, do you think that one man did all these things?" she asks.

Irene thinks, "In 1914 he was 'John Harrington.' Thirty years later he was still 'John Harrington,' but he was completely different"

Emily, in the kitchen, reaches into a pocket and pulls out some change. She reaches over to drop it in her penny jar and hesitates a second before dropping them in. The jar is nearly halfway empty. She makes a glance into the living room and sees Irene sitting there, watching television. Emily walks in there and sits down near the TV. She has a part of the newspaper in her hands, the TV schedule, and attempts to read it from the glow of the set. She reaches over to turn on the lamp next to her but it will not turn on when she switches it. She sets the TV schedule down.

The light from the TV glows and dims in their faces. Irene has one side of her headphones bent back so she can hear the TV. A narrator says, "Many of the men of Butte, especially the miners, dreamed of saving enough money to buy passage on a ship back to their homes in the old country. Work in the mines was dangerous and hard, and for those miners who made it past the cave-ins and other mine disasters there was the prospect of a slow death from lung disease." We see photographs of miners deep below the earth and photographs taken in Hospitals of men looking far older than their years and wasted away. We hear other voices speaking about the hard work of mining, and we hear about the recreation that miners and their families engaged in. We hear about Miner's Day at Columbia Gardens, and about the feats of strength that the miners engaged in. We see objects from the Mining Museum and we see Frank rolling up his sleeves and grabbing a shovel in order to compete in the mucking competition, a competition to show how quickly a man could shovel a ton of rock. We hear about the hard work of the women of Butte, preparing the picnic feasts for the Miner's Days, and about the parades that showed off the families and the benevolence of the supreme Anaconda Company.

The television glows in Emily's face. She twitches along with the program, with the voices describing the Miner's Day events at Columbia Park, at the sound effect cheers and band music. Frank walks into the house and glances at the TV screen. Emily says, "Let's all three go on a picnic."

The three walk on dead ground near a towering gallows frame. Emily stops and the other two, who were walking at her sides, go on, not because they didnít want to stop but more because they didnít notice that Emily did. Irene wears the headphones fully on both ears and Frank wears his minerís clothes. He has a shovel slung over his shoulder as if it were a rifle or a bag.

"Donít you think this is the place?" Emily asks, but then answers herself before the two others can turn around. "No," she says, and walks on, though in a slightly different direction than the other two. She stops and begins to unfurl the blanket that she has stowed under her arm but then thinks better of it by the time the other two get to her and says, "No, this is not right." She walks a few more steps and starts to wave the blanket while the other two remain where they are. As she waves the blanket, Emily sees them and says, "You do think thatís a better place, donít you." Frank shrugs his shoulders and Irene just looks puzzled. Sheís carrying a picnic basket. She canít really hear Emily because the radio is playing in her ears.

Emily points a little in another direction. "How about there?" and she heads off, with the other two behind. She unfurls the blanket over one spot and by the time it has touched the ground she has lifted it up again and moved it over about three feet, in a spot where it covers several low plants. By the time she has spread it out you can clearly see several lumps under it and she moves as if to lift it and move it again but Irene has set the picnic basket on it and sits down herself just as Emily grabs a corner. Emily holds the corner for a bit until she clearly registers that Irene has sat on the blanket and will not move before she releases the corner. She still stands as Frank sits beside Irene on the blanket.

Emily looks nervously up at the mountain above them now and again. Frank and Irene slowly look up and see Emily standing and nervous and they pull themselves back up on their feet while Emily sits down on the blanket and begins to take things out of the picnic basket.

Irene walks a few steps away and kicks at the ground, which has a strange look about it. Frank, meanwhile is looking at the ground himself, and picks up a piece of rock and turns it in his hands. Emily is now confidently eating a sandwich with her chin held high. As she chews, her eyes are firmly glued on the mountain atop which sits the white speck of a statue.

Irene notices that Emily is looking up. "What do you see?" Irene asks her and Emily continues to munch as Irene looks up too. "Are you looking at the mountain, or whatís on it?" Irene says as she scans the side of the mountain with her own eyes. When her eyes come to gaze upon the spot of the statue of Our Lady of the Rockies, Emily answers, "Iím just keeping an eye on the Our Lady." She hands Irene a sandwich while Frank examines his rock nearby.

Irene listens to a narrator on the radio describes the state of mining in Butte in 1917. This was at the height of mining in Butte. The city was bustling as it never had and as it never would again. Thousands of men labored around the clock to mine minerals out of the rock far beneath the city. Their work was especially important because of the United Statesí involvement in World War and the intense need for the wealth of raw materials under Butte to help the war effort. We hear bits of patriotic songs from the time as the hard work of mining is described, how the miners were dropped hundreds of feet below the earthís surface in small shaky elevators, and about what things were like when the miners got to their stations -- darkness lit by the flames on the helmets that the miners wore and hundreds of feet of rock above their head held in place by cracking and soggy timbers. The many mines underneath the hill of the city passed through the rich veins of ore and many of the competing mines intersected, with only gates set up to mark the end of one claim and the beginning of another.

Irene turns up the radio and watches her companions eat their lunches as if in slow motion. The sounds of the radio report come louder. A minerís carbide lamp ignites a gas-soaked rope and a fire starts. The fire spreads quickly through the underground chambers of the Speculator Mine and spread to other shafts of mines on Granite Mountain.

As we hear about the spreading of the fire, the three solemnly pack up the blanket and walk in a row away from their picnic spot. The huge rusty gallowsí frame towers over them. Emily holds an old-fashioned transistor radio to her ear and listens to the same report that Irene hears on her headphones. Frank leans over toward Emily as he walks to try to hear it better.

The fire raged through the labyrinth of mine shafts, eating up all the oxygen as it went, leaving in its wake thick clouds of smoke that were impossible for lungs. Scores of men choked far under the earth and died, others found themselves trapped under rock that fell as brittle timbers caught fire and surrendered to the rock they had held up for such a time. Some men found themselves trapped in shafts that suddenly came to an end. If the air was halfway breathable they might have a chance to survive for a few minutes or hours.

Frank, Irene and Emily reach the Granite Mountain Mine Disaster Memorial as voices on the radio describe the situation of trapped miners and the rescue teams that were trying their best to seek out whatever survivors might be still somewhere trapped in the heart of the burning Butte mountain. The three of them walk around the small monument, looking at the images of mining cut out of strips of copper and brushing their eyes over the plaques that describe the tragedy. Their eyes tilt up to look at the scene of the disaster, the gallowsí frames that still mark the mines that were touched by the disaster that day. Irene says, "I think my great grandfather was killed in the disaster," and she points at a name on one of the plaques. Emily and Frank look over her shoulder. Frank looks especially interested.

Irene points to a Gallowsí Frame, "That must be the Speculator," she says. Frank follows her finger and says, "No, the Speculatorís there. That frame belongs to the Mountain Con." Irene and Frank stand close together and move from one segment of the Mine Disaster display to another as Emily steps back from the monument, looks up at the mountain above them, and falls down on her knees, not so much in prayer as in despair.

On to Part three.